We want to tell the story of integration from a “start with a derivative” perspective.

Let’s start by making you (the reader) the function y=x and we’ll give you the nickname “ex”.

Yes, you are a function.

Here’s the deal–you are somebody’s derivative. That’s right, some function somewhere says “yeah, ex is my derivative”. That means you hold a knowledge of the point slope for point on that unknown function. Taking that further for any point (x,y) that you have, the slope through that point is m=x (m is the traditional symbol for a slope) and we will need this fact. Later we will have a point like (x1,y1) and you have to remember that the slope at that point is x1.

[Appendix A tells you the answer, it is fine to go there now to find it]

We are going to play a game and hopefully at some point you will see what we are doing (and why).

We are going to start at (0,0).

Recall that a slope (m) is and if we know everything except

we can calculate it.

We are not required to work equal length intervals but it will probably make the math easier.

We are going to want to create a function that goes from (0,0) to a point where x=1. For now, call that point (1,b) and think of b as being a placeholder.

We need to decide how many intervals we have. We are going to say 4. If a length of 1 is broken into 4 intervals then each interval has a width of 0.25 and so our first segment will be a line segment from (0,0) to (0.25, ?).

The slope at (0,0) is 0 and so when we to the algebra we get…

m = \dfrac {y_2 – y_1}{x_2 – x_1} \to 0 = \dfrac {0 – 0}{0.25 – 0} [/latex]

From this we went from the point (0, 0) to (0.25, 0). We need to repeat the process for finding the point (0.5, ?).

m = \dfrac {y_2 – y_1}{x_2 – x_1} \to 0.25 = \dfrac {0.0625 – 0}{0.5 – 0.25} [/latex]

Now we know the next point is (0.5, 0.0625). We need to repeat the process for finding the point (0.75, ?).

m = \dfrac {y_2 – y_1}{x_2 – x_1} \to 0.5 = \dfrac {0.1875- 0.0625}{0.75 – 0.5} [/latex]

Now we know the next poit is (0.75, 0.1875). We need to repeat the process for finding the last point (1, ?).

m = \dfrac {y_2 – y_1}{x_2 – x_1} \to 0.75 = \dfrac {0.375- 0.1875}{1 – 0.75} [/latex]

It was tedious and laborious to do the work just to get one example with only four pieces in it.

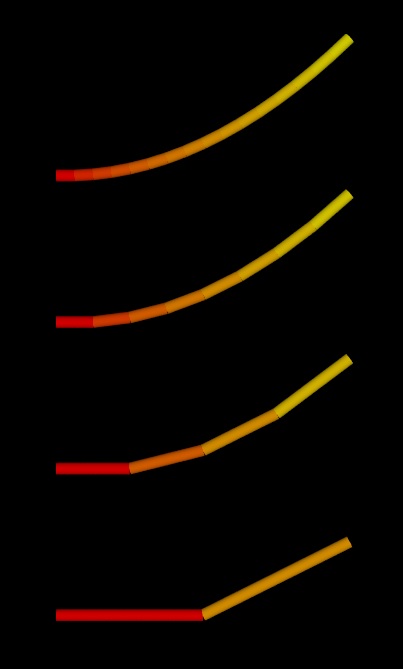

We believe you will agree that we want to use the above to check a computer program and then let the computer process dozens of examples, possibly some with hundreds or thousands of pieces. The picture for this blog shows this work down with 2,4,8 and 16 pieces.

Work was done with a different computer program. This time it was just “math”, no work with computer graphics. Below is what the computer told me (keep in mind we know the correct answer is 0.5):

I reckoned 0.25 for 2 and 0.5 – 0.25 is 0.25

I reckoned 0.375 for 4 and 0.5 – 0.375 is 0.125

I reckoned 0.4375 for 8 and 0.5 – 0.4375 is 0.0625

I reckoned 0.46875 for 16 and 0.5 – 0.46875 is 0.03125

I reckoned 0.484375 for 32 and 0.5 – 0.484375 is 0.015625

I reckoned 0.4921875 for 64 and 0.5 – 0.4921875 is 0.0078125

I reckoned 0.49609375 for 128 and 0.5 – 0.49609375 is 0.00390625

I reckoned 0.498046875 for 256 and 0.5 – 0.498046875 is 0.001953125

The key thing to notice here is that every time we double the number of iterations the difference between our calculation and 0.5 is cut in half. With that in mind please remember what Newton said:

Quantities, and the ratios of quantities, which in any finite time converge continually to equality, and before the end of that time approach nearer the one to the other than by any given difference, become ultimately equal.

We paraphrase the above to “if you get as close as you want while following the rules, you are approaching the limit!”

We can get as close as we want because we can keep halving the difference until we have a difference smaller than “how close we wanted to approach”.

Appendix A

From work done elsewhere we know that if our function is…

…then the derivative of our function is…