A set of vectors may be used as a Basis for a Vector Space if every vector in the Vector Space may be represented as a Linear Combination of the vectors in the set.

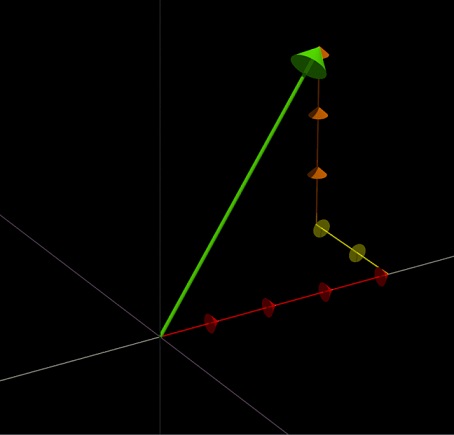

We can provide an example of this where we use the three vectors below as a Basis:

,

,

We can express the vector as a linear combination of the above three vectors:

The part about being a Linear Combination involves a summation of terms with each term being one of the vectors multiplied by a scalar.

The three vectors chosen above to be basis vectors for a three dimensional vector space is the most common choice. Each vector has a length of one and each vector is orthogonal to both of the other two vectors.

The choice to have basis vectors that comply with the rules of an Orthonormal Basis Set provides convenience.

We can legally make other choices, as long as we follow two rules:

- The number of vectors in the basis set has to equal the number of dimensions in the vector.

- It is not allowed for one basis vector to be a multiple of another basis vector or a linear combination of basis vectors. For example, if one vector is [1,2] then another vector being [2,4] is not allowed.