Assume we live in a universe where the unit of length is the centimeter. We can draw up our Basis Vectors as being the following:

Someone comes along and wants basis vectors to use for inches. After some discussion to make certain we understand him, we tell him that his basis vectors will have a length that is 2.54 the length of the our basis vectors. We put a tilde symbol over each of his basis vectors so we can recognize it isn’t one of ours.

We share something in common with our new friend, we are both using basis vectors where each vector is orthogonal to the other two vectors. This leads to simpler math, and we want that simple math. Unfortunately, that math can make it appear, to a new student, that we don’t need a matrix to transform from one basis set to another. Appendix A shows a transformation where all four components of the transformation matrix are used. With that in mind, we can continue with our transformation from a centimeters basis set to an inches basis set.

This matrix, , can process all three basis vectors at the same time:

The trick to interpreting the above math is to realize that, for the matrix on the right, each row in the matrix is one of the new basis vectors.

Now, we could change the story, and say that we begin where our friend works, and everyone is using inches, so our original vectors with zero and one values correspond to inches. Assume we go to that place, and they want to do a transform to go from their basis set (in inches) to the one that we want to use, centimeters. This time we get from the original basis vectors to the new basis vectors by dividing by 2.54 cm:

For the work below showing the conversion from inches basis set vectors to centimeters basis set vectors, we will use both sides of the equality . Also, 1 inch is exactly 2.54 centimeters so we aren’t limited to 3 significant figures.

If we do that trick of packing basis vectors into a matrix, we get the following:

The two transform matrices are such that one undoes the change of the other. Recall your studies of algebra where a+(-a)=0 and a*(1/a)=1 and recall that 0 is the Identity Element for Addition and 1 is the identity element for Multiplication. We have something similar, which is shown below:

where

is the identity matrix.

Because one matrix multiplied by the other results in the Identity Matrix (I), we say that one matrix is the Inverse Matrix of the other.

Appendix A

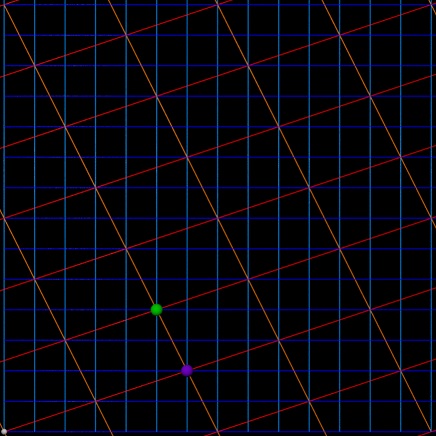

Basis vectors do not need to be orthogonal. We can consider a situation where they are not. We’re going to temporarily go back to two dimensions to make the math simpler–and after we figure it out we’ll move our ideas to three dimensions.

In the graphic below, bluish lines come from orthonormal axes x and y. The red and orange lines come from “alternative axes” x’ and y’ which are not orthonormal.

- Purple Point

- (x,y) = (6,2)

- (x’,y’) = (2,0)

- Green Point

- (x,y) = (5,4)

- (x’,y’) = (2,1)

With the data from these two points we can calculate the matrix that will take (6,2) to (2,0) and (5,4) to (2,1):

In the math below, a,b,c,d are unknown variables that we need to solve:

We can derive two sets of simultaneous equations from the above two equations:

- 6a + 2c = 2

- 5a + 4c = 2

and

- 6b + 2d = 0

- 5b + 4d = 1

Doing the math for these leads to

- a=2/7

- b=- 1/7

- c=1/7

- d=3/7

- and

- putting this together gives us a transformati

We put these together:

We can test this. We go back to the graphic and find there is intersection of integer points at (x,y)=(6,9). We test this with the matrix:

We go back to the graph and find that (x,y)=(6,9) corresponds to (x’,y’)=(3,3) as is predicted by our transformation matrix.

The work leading to the matrix for transforming in the opposite direction leads to:

Appendix B

For truth to be maintained, if one of the matrices above is used to change the basis vectors then the other matrix needs to be use to change the components.

This is a truth for any transformation: The tensor that changes the basis vectors multiplied by the tensor that changes the components equals the identity tensor.

One thing that doesn’t show up in this work: let a be the Matrix that transforms the basis vectors. Let B be the matrix that transforms t

Appendix C

prjn = projection