Introduction

This first part will try to introduce the idea of a vector as simply as could be possible. After that, will be mentioned in a second section, “More Theory”.

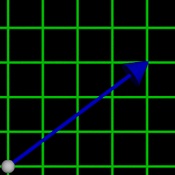

We can create a vector that starts at the origin, (0,0), and goes to a point of interest (4,3). We can put the vector on a grid (like graph paper).

A vector has a direction and a magnitude. We haven’t defined or explained either, but hopeful you can see the two ideas.

More Theory

A vector can be defined as the combination of a length (magnitude) and a direction.

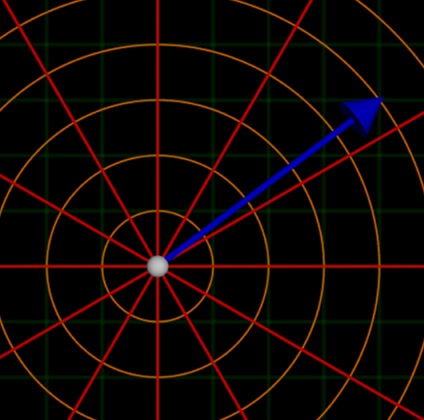

If we switch from Cartesian Coordinates to Polar Coordinates, one of the components provides us with the length of the vector (5 units) and the other coordinate provides the direction. Our example vector is pointed at about 39.37 degrees if 0 degrees is the ray to the right of the origin and angle increases in a counterclockwise direction.

Direction is a primitive notion that must be understood intuitively–we cannot define it further.

Length may be understood as a quantity with units. The importance of the units may be understood after noticing that two different numbers may represent the same length. An example is shown below:

- 1 inch

- 2.54 centimeters

It is tradition for a single dimension to be represented as a number line heading either “east” and “west”.

- Numbers east of zero are positive

- Numbers west of zero are negative

Does it make sense that the negative sign is just telling you the direction?

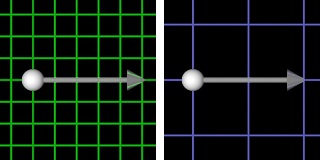

A vector is shown below, scaled to 2 inches (inches is blue). Can you see that it is the same vector? In this scenario we are saying that the vectors are the same length and we are using size on your computer screen as the standard for this assertion.

It is tradition for a vector to be drawn on graph paper with spacing between adjacent parallel lines corresponding to a unit of length. In your beginning work with vectors you probably won’t bother to define your unit length with a word like “inch” or “centimeter”. It’s important to know that you are still using a unit length. This idea will come out when you start working with Tensors.

2 in = 5.08 cm

Appendix A : Further Topics in Vectors

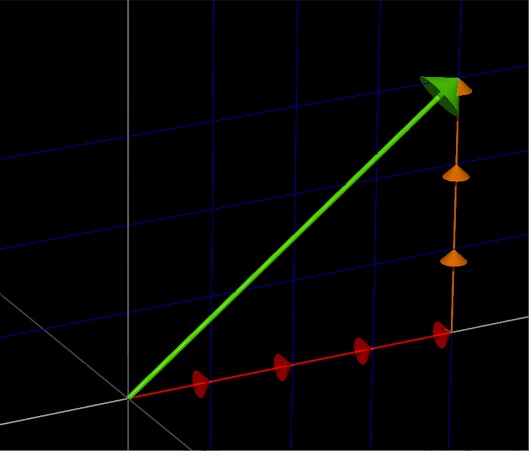

Vectors can be added easily in a Cartesian Coordinate system. In fact, it might be helpful to think of a vector as being built in the following way:

(1,0) + (1,0) + (1,0) + (1,0) + (0,1) + (0,1) + (0,1) = (4,3)

Work is in progress on an editorial about Invariance and Integrity.

Appendix B

A vector doesn’t have a frame of reference. That statement may seem confusing because when you look at it you see an intersection on the graph paper where the vector started.

No frame of reference means we don’t know what numbers correspond to that point. It would make sense to start it at the origin, but we could start it at another location if we have reason to do so.

In one example, we are doing vector addition and the second vector must start at the head of the first vector.

Appendix C

The Informal Discussions provide more insight into vectors.

References: